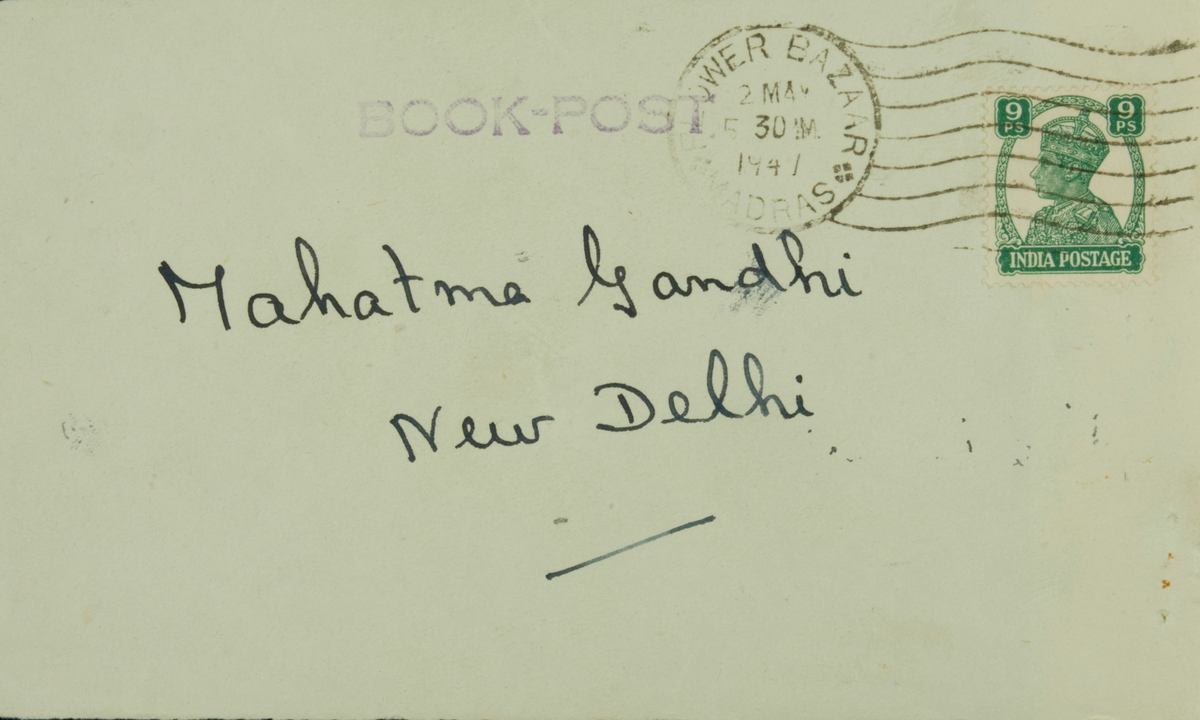

On 2 June 1947, one day before the outgoing British Raj formally announced it would cleave its Indian territory into two new nation states, its viceroy Lord Mountbatten met with Mahatma Gandhi to negotiate the imminent plans. Not much is known about this discussion, though its scope was likely limited by the fact that it fell on a Monday, the one day of the week that Gandhi undertook a vow of silence.

Unable to communicate by speech, the Indian activist leader, who would be assassinated seven months later, wrote Mountbatten five letters on the backs of used envelopes. On them he said: “When I took the decision about the Monday silence I did reserve two exceptions, i.e. about speaking to high functionaries on urgent matters or attending upon sick people. But I know you don’t want me to break my silence…”

Installation view of Tangled Hierarchy, John Hansard Gallery. Photo: Thierry Bal

These five rarely displayed artefacts now form the focal point of a contemporary art exhibition at John Hansard Gallery in Southampton. Tangled Hierarchy (until 19 September) is curated by the Mumbai-based Jitish Kallat, who was invited by the gallery to consider these letters within a group show around language, borders and loss, which coincides with the 75th anniversary of partition.

“We don’t know what Mountbatten said that day,” Kallat says. “But in his silence Gandhi leaves us an archival residue from a moment just weeks before one of the largest human displacements in history. They open numerous questions about speech and silence, agency and hierarchy. Was his silence a result of his already having expended his words challenging partition? We can only speculate…”

Mona Hatoum’s installation Map (mobile) at Tangled Hierarchy, John Hansard Gallery. Photo: Thierry Bal

For the show, he has brought together works by artists such as Kader Attia, who shows a new film, and the late artist Zarina, known for her sparse drawings of maps and floorplans. Two works by the British Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum are also included: a fragmented world map made of glass that is suspended from a mobile, and sculptural installation featuring a paper map, cut up and refashioned into a bag.

They join non-art historical artefacts and scientific tools such as trunks used by displaced people during partition and loaned from the Partition Museum in Amritsar, India. A mirrored box designed by the neuroscientist V. Ramachandran, which is used to treat post-amputation patients experiencing phantom limb pain by creating the illusion of two limbs, is also included in the show. Along with several other works, it is used to discuss themes of loss, ownership and the after-effects of trauma.

Jitish Kallat’s installation Covering Letter (2022). Photo: Thierry Bal

Kallat also shows his new immersive installation work, Covering Letter, that projects onto a curtain of fog the words from a letter written by Gandhi to Adolf Hitler just weeks before the start of the Second World War. That letter begins with the words: “Dear friend”, an unsuccessful plea from an advocate of non-violence to one of history’s most violent individuals.

While the show was not intended to coincide with the 75th anniversary of partition, Covid-related delays presented the opportunity to tie it to the historic moment. But Kallat says he hopes for the exhibition to extend past Gandhi or partition, and allow us to consider how acts of division and war continue into the present day.

“As we reflect upon the historic Gandhi notes, we find ourselves once again in a tangled hierarchy—a world caught in a strange recursive loop—where a tragic human displacement of a scale similar to that of the Indian partition is currently unravelling in Ukraine,” Kallat says. “It again comes back to the eternal return of human tragedy—or human folly—and aggression.”