Van Gogh’s life has been pored over by so many writers that it is rare for new documentary evidence to emerge. But among recent discoveries is a bulky register that records the patients admitted to the asylum where the artist stayed for a year, after he mutilated his ear. The full story is in my book Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum, which is coming out in paperback.

Martin Bailey’s Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (paperback edition of the original 2018 publication) Credit: Frances Lincoln/Quarto

Following a tip-off a few years ago, I travelled to the southern French town of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, accompanied by a friend and researcher, Onelia Cardettini. We had heard that the local archive had acquired a register of the asylum, but had little idea what it would contain. It turned out to be a large volume bound in mottled paper, recording the arrival of hundreds of patients.

Register of admissions (1876-92) at the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence Credit: Archives Municipales, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence

We rushed to look at the entries for 1889, spotting the arrival of the asylum’s most illustrious patient. It recorded that Vincent van Gogh had been born in Holland, was then aged 36, and had travelled from nearby Arles on 8 May. The date of Van Gogh’s arrival had long been known, but we quickly realised that the newly unearthed register should make it possible to identify the artist’s fellow patients.

Entries in the register of admissions at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole in 1889, including Van Gogh’s name (indicated in red) Credit: Archives Municipales, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence

Until now most biographers of Van Gogh have given comparatively little attention to the impact that living among these disturbed people must have had on the artist. He would be with them in the common room, the refectory and the garden—and even when alone in his bedroom he was unable to escape the screams and howls.

The asylum, established in the former monastery of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, would have been nothing remotely like a modern psychiatric hospital. At that time little was known about mental illnesses and even less about what could be done to treat people or alleviate their condition.

There were only 18 male patients at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole when Vincent arrived. He lived in this small community for a full year, sharing their sufferings. Getting to know the men well, Vincent described them on several occasions as “my companions in misfortune”.

Life must have been extremely stressful. Vincent wrote to his brother Theo that “the room where we stay on rainy days is like a 3rd-class waiting room in some stagnant village”. What struck him most forcibly was the men’s boredom and sluggishness.

The admissions register contains no medical data, but with the names of the other patients it proved possible to use other sources to research their varied backgrounds and conditions. I was shocked to discover quite how ill most of them were—and what a challenging environment this must have created for the artist.

Vincent wrote that “one continually hears shouts and terrible howls as though of the animals in a menagerie”. Four months after his arrival, he confessed to his brother that “I’m afraid of the other patients”.

Further research revealed disturbing details about the condition of some of the men. Their individual stories give us an insight into their suffering, although it does make for distressing reading.

Jean R. was 20 years old when he arrived in 1887, two years before Van Gogh. He had never learned to speak and was prone to acts of violence—hardly surprisingly, since he was unable to communicate verbally.

Jean ended up being the last male patient in the asylum, which only accepted females after the First World War. In his last years, he would usually sit by the entrance lodge of the asylum. Jean died in 1932, aged 65—after living for 45 years behind its walls.

Vincent was presumably referring to Jean when he wrote to Theo about an unnamed patient “who doesn’t reply except in incoherent sounds”. Vincent told Theo that the man only responded to him “because he isn’t afraid of me”, suggesting that the artist went to considerable efforts to be sensitive and understanding.

Twenty-six-year-old Joachim R. had been admitted in February 1889, three months before Van Gogh. Medical reports at the time categorised him as “a true suicidal monomaniac”. He is not recorded at the asylum in the 1891 census, so by then he could have been moved elsewhere—or he might possibly have died tragically young.

Henri E., aged 40, was admitted just two weeks after Van Gogh. Vincent wrote to Theo: “A new person has arrived who is so agitated that he breaks everything and shouts day and night, he also tears the straitjackets and up to now he scarcely calms down, although he’s in a bath all day long, he demolishes his bed and all the rest in his room, overturns his food etc. It’s very sad to see—but they have a lot of patience here.”

Antoine S., aged 76, was a retired priest who had been living at the nearby monastery of Saint-Michel-de-Frigolet. He may well have been suffering from dementia.

Eating together and observing his companions, Van Gogh must quickly have had the idea of painting portraits of these unusual characters—or at least the more amenable men who were able to sit still.

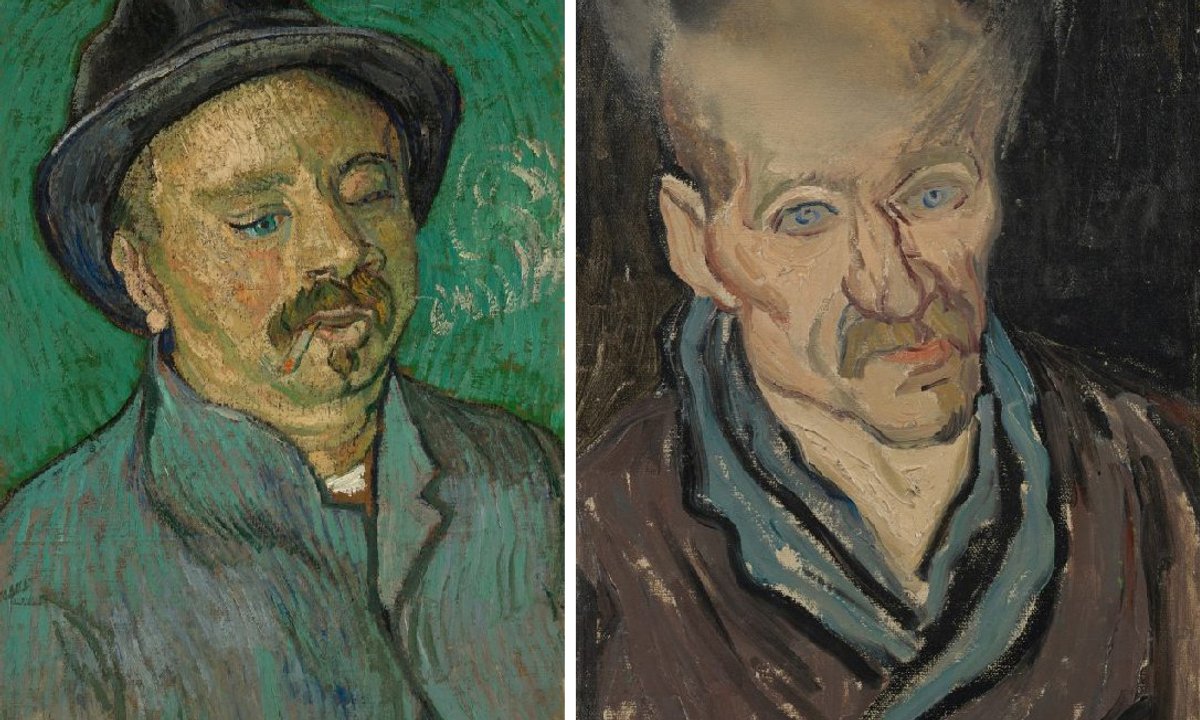

Van Gogh’s Portrait of a Man with a Cigarette (autumn 1889) Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Portrait of a Man with a Cigarette is often said to depict a patient with only one eye, but in fact the sitter appears to have been suffering from a drooping eyelid, a condition known as ptosis. It was courageous of someone with such a condition to have posed for a portrait, particularly as Van Gogh made no effort to disguise their affliction.

Perhaps the sitter and the artist, who was even more disfigured (after the mutilation of his ear), felt a common bond. In October 1889 Vincent wrote to his mother that he was working on “a portrait of one of the patients”, most likely this one. Referring to his companions, Vincent added that “it’s strange that when one is with them for some time and is used to them, one no longer thinks about their being mad”.

Van Gogh’s Portrait of a Man (autumn 1889) Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Van Gogh’s disturbing Portrait of a Man depicts an elderly patient. This sketchy, expressionist and rather crude image has at some point suffered deterioration in the forehead area, giving the sitter’s gaunt face an even more sorrowful appearance.

Although something of an artistic failure, this unnerving portrait—which has rarely been exhibited and is relatively little known—tellingly reveals much about the reality of asylum life. The man’s empty-looking eyes betray a deep sadness and sense of incomprehension.

It is heartbreaking to think of Van Gogh living among such troubled patients. And it is difficult to conceive of an artist being able to create such vibrant and optimistic paintings surrounded by such distress. Van Gogh was well aware of the dangers: “What would be infinitely worse is to let myself slide into the state of my companions in misfortune who do nothing all day, week, month, year.”

Van Gogh’s Window in the Studio (September–October 1889) Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

But it was art that actually saved Van Gogh and made life tolerable. Along with his bedroom, he was allocated another room for his studio, a retreat where he could apply his creative talents—and try to forget where he was living. But as he looked out of his studio window, the view would be interrupted by bars.

After recovering from a mental crisis in April 1890 Van Gogh was more determined than ever to leave. Looking back, he later wrote: “My last crisis, which was terrible, was due in considerable part to the influence of the other patients, anyway, the prison was crushing me”. Vincent explained in a deeply felt letter: “The surroundings here are starting to weigh on me more than I could express… I need air, I feel damaged by boredom and grief.”

But was at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole that Van Gogh created some of his most memorable paintings—the wheatfield that he looked down on from his bedroom, the soaring cypresses, the ancient olive groves beneath Les Alpilles, his greatest self-portrait. And of course his most inspirational asylum painting, Starry Night—his personal vision of the heavens.

Van Gogh’s Starry Night (June 1889) Credit: Museum of Modern Art, New York

In May 1890, a year after his arrival, Vincent left Saint-Paul-de-Mausole. His doctor then categorised him as “cured”, but sadly that was hardly the case. Three months later, in a wheatfield on the outskirts of Auvers-sur-Oise, he ended his life.

Other Van Gogh news:

Maryna Savchenko’s painting (2016) of the actor Eleanor Tomlinson, who plays Adeline Ravoux, the daughter of Van Gogh’s landlord in Auvers-sur-Oise, in the animated film Loving Vincent (2017) Credit: Loving Vincent Art Auction in aid of Ukrainian Children

• Two of the paintings used in the animated film Loving Vincent are to be auctioned to benefit a Ukrainian charity based in Poland. Ending on 24 September, the online sale is being organised by the Polish-Based BreakThru Films—and it will support the Fundacja Rozwoju Dzieci, which runs 100 childcare centres for Ukrainian refugees.

Reconstruction (2023) of the lost image of Van Gogh’s hidden painting of two wrestlers and his Self-portrait with Grey Felt Hat (September-October 1887) Credits: Oxia Palus, London and Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

• A London company, Oxia Palus, has published a reconstruction of a lost Van Gogh image, which was later overpainted on the canvas as a flower picture (Still Life with Meadow Flowers and Roses, 1886-87, now at the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo). A decade ago, x-rays revealed that underneath the still life was an earlier composition of two boxers, which is referred to in a letter from Vincent to his brother Theo written in Antwerp in January 1886.

The Oxia Palus reconstruction was done by neuroscientist Anthony Bourached and physicist George Cann of University College London. However, the resulting image gives only a rough approximation of Van Gogh’s lost work. The crude brushwork of the reconstruction seems unlike that of Van Gogh and the colours and background patterning are more reminiscent of his self-portrait painted in Paris in September-October 1887 after his technique had developed, not his earlier Antwerp style.