Sonia Boyce: Just for the Record, Simon Lee Gallery, until 16 December

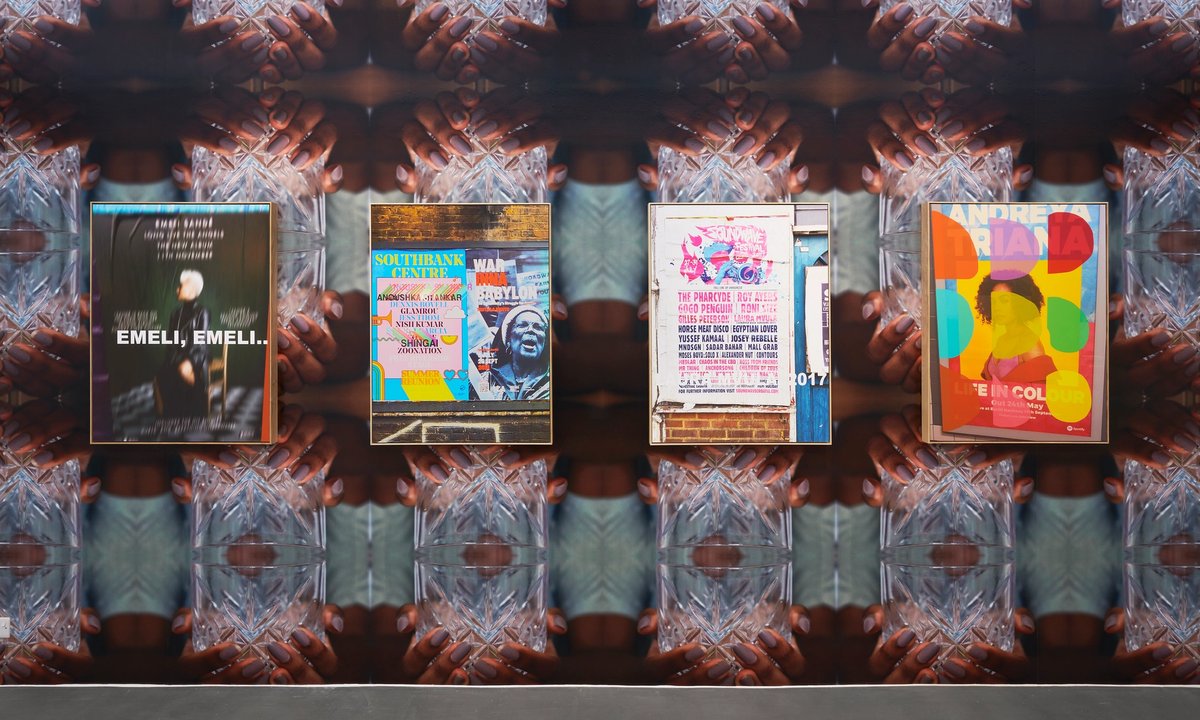

A key member of the pioneering British Black Arts movement and the first Black woman artist to both enter the Tate collection and represent Britain at the Venice Biennale, Sonia Boyce’s first-ever commercial solo show is now on at Simon Lee Gallery (which began representing her in May 2021). Just for the Record presents new works riffing off the artist’s decades-long project Devotional (1999-present) which has brought together memorabilia celebrating Black British women in music, from punk band X-ray Spex’s Poly Styrene to rapper Ms. Dynamite.

The new exhibition transforms the memorabilia—here, worn records—into commemorative sculpture. It also includes concert posters from musicians included in Devotional. As photos of found objects, the posters commemorate a time when the musician was widely celebrated—which may or may not have passed. In some ways, the atmosphere is melancholic. But, as the exhibition title suggests, their inclusion in this show also allows the singers, rappers and emcees to take their rightful place in the records of Black British music history.

Tyler Mitchell: Chrysalis, Gagosian, until 12 November

In Christina Sharpe’s seminal text on race, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016), respite from the ever-present “weather” of anti-Blackness is a radical and often unattainable ideal. Here, small pockets of rest and leisure—already unevenly distributed along race and class lines—become charged. These contemplations hang heavy in the air at Tyler Mitchell’s first solo show in the UK, with its delicate photographs of Black people in repose.

The greenery, present in both the landscape and studio props, presents the American south as quaint idyll as well as historic slave plantation. For Mitchell’s isolated subjects, however, their surroundings provide a cocoon or chrysalis. Sleeping and protected by mosquito nets, in front of a painted garden photo backdrop, suspended in time in a tire swing over calm waters—the works slip into the realms of dreams and utopia.

Ufuoma Essi: Is My Living in Vain, Gasworks, until 18 December

In the latest exhibition at Gasworks in South London, the seat that viewers are invited to use is in fact a pew. Indeed, watching Ufuoma Essi’s new film on the Black Church, it becomes difficult to separate the act of viewing worship from participating in it. To this end, the film occasionally interposes footage of liturgy and song to create an overwhelming sensory environment, underscoring the embodied experience of worship.

Essi’s work is also concerned with the Black Atlantic, a multinational understanding of Blackness popularised by the cultural theorist Paul Gilroy. Footage and sounds of West Philadelphia and London’s Brixton (both archival and shot on location) are projected onto one another to explore topics such as diaspora, community and belonging.

Photo: © Jo Underhill, courtesy Serpentine

Barbara Chase-Riboud: Infinite Folds, Serpentine, until 29 January 2023

Imposing large-scale sculptures, wrought from masses of bronze, aluminium, wool and silk are at the centre of Chase-Riboud’s first solo show in the UK. Spanning the seven decades of her career, the exhibition offers a look at the early elements of her practice, as in the figurative Walking Angel (1962), as well as the later development of abstraction.

Highlights include the Malcolm X Steles (1969) where sculpture’s ambitious role in commemorating larger-than-life figures is explored; “I sculpt what I can’t write,” the artist told the Financial Times earlier this month. The show also looks at the artist’s work in commemorating overlooked figures. La Musica Josephine/Red Black (2021) is dedicated to Josephine Baker, the Black French-American dancer and civil rights activist who in 2021 became the first Black woman to enter France’s Pantheon mausoleum.

Installation view, Andy Stagg. Courtesy of South London Gallery

Simeon Barclay: In the Name of the Father, South London Gallery, until 27 November

Erected structures and doors, sculptures, moving image and neon light installations comprise Simeon Barclay latest institutional show, which is concerned with inheritance, both familial and cultural. Personal histories—such as his father’s work as a tailor and the artist’s former job as an industrial machinist—are woven together with shared cultural memories. These include the 1979 British cult movie Scum and the landscape and industrial past of Yorkshire (where the artist grew up). Sculptures also make reference to the legacy of art historical behemoths such as Joseph Beuys and Alexander Calder. With its allusions to Huddersfield’s social geography—including the infamous and exclusive nightclub Johnny’s—Barclay brings into focus questions about place, identity and inclusion.

Photo: Chinma Johnson-Nwosu

Amy Sherald: The World We Make, Hauser & Wirth, until 23 December

At American portraitist Amy Sherald’s first European show, in the far corner of the second room, is a striking portrait of Sherald’s nephew. He was meant for all things to meet (2022) depicts the boy against a luminous green backdrop, with the bright-white emblazoned “22” on his varsity jumper taking on the quality of regalia. However, with Sherald’s characteristic absence of place and use of grisaille, the work resists easy interpretation as a commemoration of “Black excellence”. It’s instead an intimate moment designed around the sitter, as the viewer is invited to contemplate his life.

We find this intimacy throughout the paintings in the exhibition. Despite its mammoth size, the diptych Deliverance (2020) draws us into the exultant moment of the bikers in the air. It’s one of the few paintings in this show (and in the artist’s oeuvre) where the subjects ignore the viewer. Instead, their gaze turns inwards; fixated on the moment they have created for themselves: suspended in euphoria, flying, free.