As details emerge of a substantial $410m insurance claim from the American banker and collector Ron Perelman, concerned with five artworks damaged in a fire, the Seoul and Busan-based Kukje gallery (and linked Tina Kim Gallery) are facing a lawsuit from the Judd foundation over “irreparable damage” to a sculpture.

Both cases remind the sector that agreeing the value and condition of artworks within insurance disputes, remains far from a clear-cut practise.

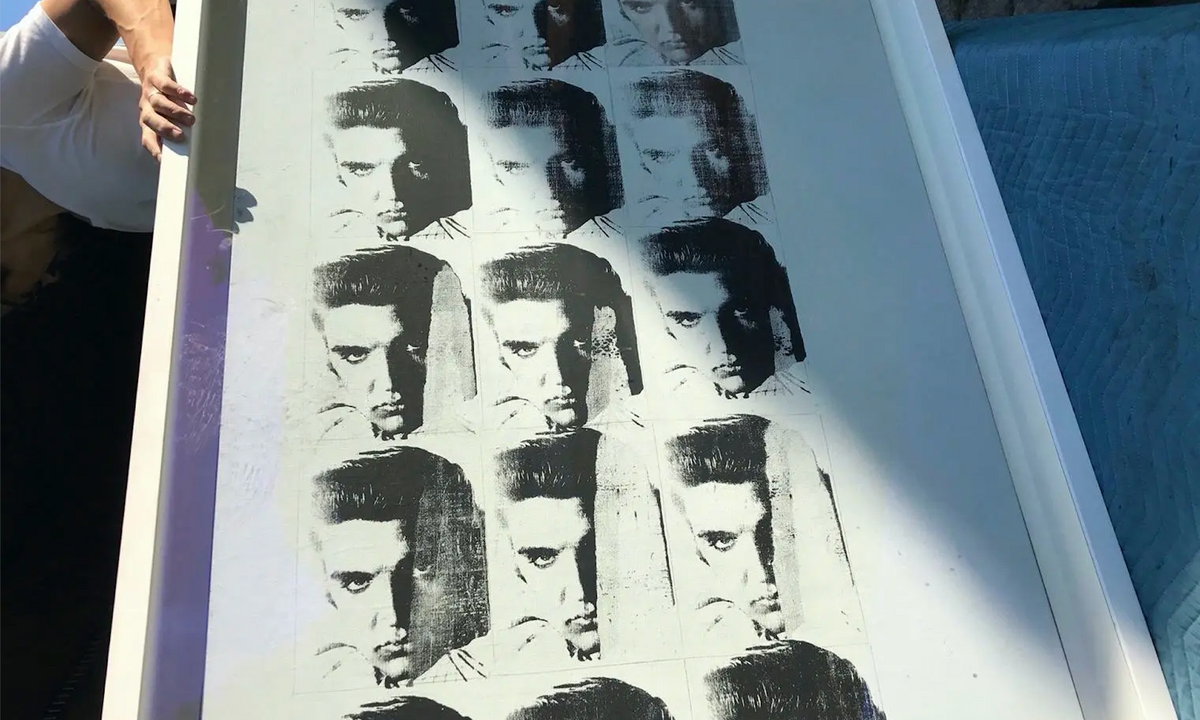

According to Artnet News, several holding companies owned by Perelman (named as AGP Holdings) are suing insurers (identified as underwriters of Lloyds of London), arguing that a number of works caught up in the 2018 fire in the banker’s East Hamptons estate, lost their “oomph”. These include works by Ed Ruscha, Andy Warhol and Cy Twombly.

Meanwhile the Judd Foundation argues that Donald Judd’s Untitled, 1991, sculpture is no longer sellable due to fingerprints left on its surface and claim that while the insurance company fulfilled its payment of 80% of the sculpture’s estimated $850,000 fair market value (as specified in the coverage) the gallery should top up the remaining amount, plus legal fees, as per the 2015 consignment agreement terms.

When is damage, truly damage?

“Such cases are becoming more common,” says David Scully, a mediator with the specialist resolution firm, ArtMediation, and author of the publication The Law and Practice of Fine Art, Jewellery and Specie Insurance (2021).

“First, there has been an increase in investment buyers, particularly in the contemporary art field, who often require their artwork to be pristine. Second, the growth of collecting, especially of sensitive contemporary art in tropical and sub-tropical area has resulted in damage that may be made worse by environmental factors, for example, a painting may be rolled incorrectly causing microscopic paint cracks into which, in a polluted and humid city, dirt may enter disfiguring the painting—or simply a sweaty hand disfiguring an artwork.”

For Perelman, the situation is complicated further by the fact that a period of time passed before damage was identified. That is, despite his confirming in public shortly after the fire (as reported by The New York Times) that the blue-chip collection was largely unharmed, with only some of the works’ suffering “minor smoke and water damage”, a year-and-a-half later he noticed that some had lost “their lustre”. The insurers are thought to have paid over $140m in the initial claim, excluding the art now in question.

Conservators and appraisal services have long assisted the market in providing neutral opinions within such disputes. Yet, the need to obtain the right specialist can prove an increasingly challenging task, given the expanding range of art works in the industry. Digital art (notably art existing purely online), for example, remains somewhat of an enigma for the industry sector, which relies on a period of trading within a market to establish value.

“Nevertheless, digital platforms and technology can also be beneficial to the claim process,” says Caroline Taylor, founder of Appraisal Bureau, which is later this month launching an app to record immutable documentation directly onto the Blockchain.

A slippery value system

Even when it is agreed who should be paying, the value of lost “oomph” can still be challenging to pin down. An October lawsuit filed by Julie and Matthew Halbower in Michigan saw the homeowners allege a breach of contract by Hiscox syndicates, for using a June 2021 valuation of the art works lost in a residential fire, rather than the more recent (and higher) 2022 valuation. Details of the works lost have not been published although court papers suggest that their value sits at “more than $20m and less than $93.56m”.

Scully notes that thinly traded markets for some artists and the high number of private sales can also make it difficult for insurers to quickly assess proposed values.

Ultimately, the resolution to such claims comes down to a balancing act of interests. As Robert Read, head of fine art and private clients at Hiscox says (in a comment unlinked to any particular case): “Given that 50% of art claims involve accidental damage, which often result in partially damaged items, this is a daily challenge […] Different experts will come up with different recommendations, the skill for art insurers is finding a reasonable number that is acceptable to all parties.”