What did the Medici, the Rothschilds and J.P. Morgan have in common? They were all bankers who forged vast artistic legacies. They are also some of the stars of a sweeping show spotlighting leading financiers and their art. Taking place at the Milan branch of the Gallerie d’Italia, the show explores the financial world’s role in producing art, and art’s role in consolidating bankers’ social status. It is a grand investigation into how, in the words of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, economic capital transforms into cultural and symbolic capital.

The exhibition covers a 500-year span—from the Medici to the Rothschilds—and a territorial sweep stretching from Europe to the US. Eleven sections, each dedicated to an individual banker, contain 120 paintings, sculptures, drawings, engravings and bronzes by artists including Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Anthony van Dyck, Angelica Kauffman and Giorgio Morandi. They include loans from the Musée du Louvre, the National Gallery in London, the Albertina in Vienna, the Staatliche Museen in Berlin and the Morgan Library and Museum in New York.

“Bankers are among the most numerous social categories of collectors in the world,” says the co-curator Fernando Mazzocca. “We have tried to show their individual tastes through the works they acquired and commissioned. What emerges is a sense of the refinedness of each collector.”

Caravaggio’s St. Jerome (around 1605-06) Montserrat, Museu de Montserrat

Well-known patrons featured include Cosimo and Lorenzo de’ Medici, the powerful grand dukes of Tuscany who funnelled enormous amounts of money into the Florentine Renaissance, and Agostino Chigi, the Sienese financier of popes for whom Raphael frescoed the Villa Farnesina in Rome. Visitors will learn that the Torlonia family, famed today for owning the largest collection of ancient sculptures currently in private hands, also commissioned art, as clear from Per un de’ piedi il furibondo Alcide afferra e scaglia Lica (1812)—“possibly [Antonio] Canova’s greatest work”, Mazzocca says.

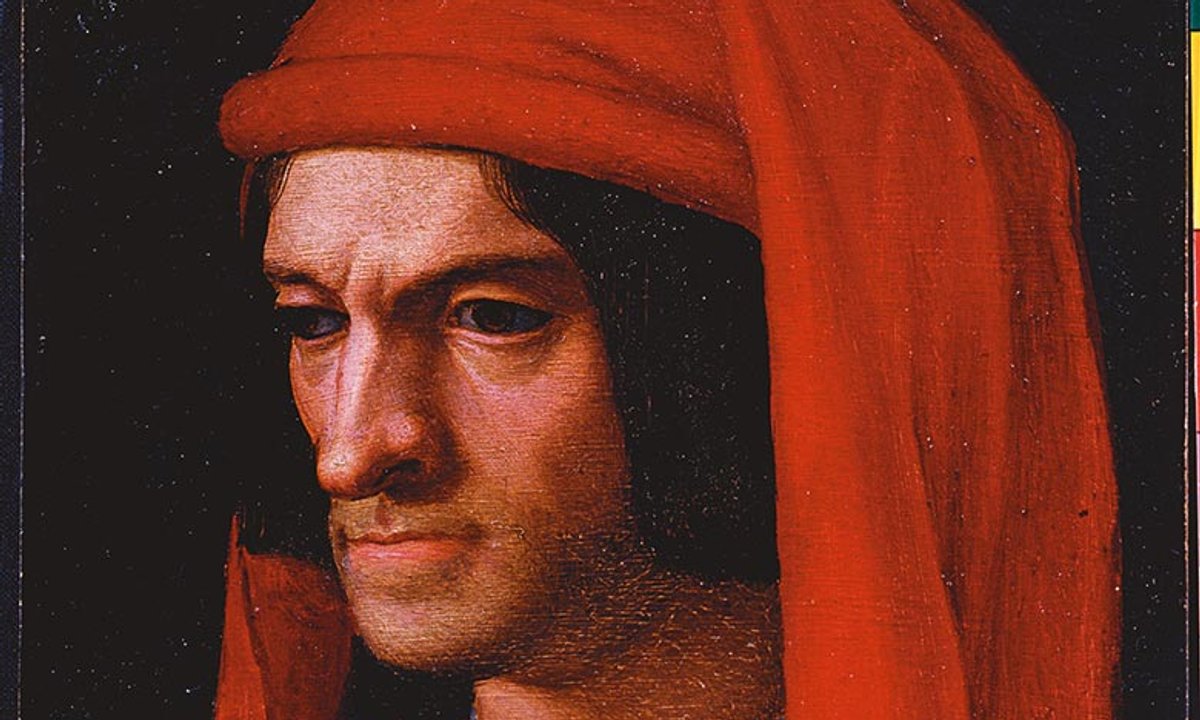

The exhibition also explores what motivated the patrons. Some, like Lorenzo de’ Medici—whose portraits and busts by the likes of Pietro Torrigiano and Bronzino are included in the show—sought personal glory. Others aimed to enrich society through art. Andrew Mellon, the US banking empire heir, started building the West Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC in 1937; following his death, his son donated around 1,000 paintings—including works by Raphael, Titian and Claude Monet—to the museum.

An accompanying catalogue includes in-depth essays assessing each banker’s legacy and detailed notes on the works. The biggest discoveries relate to the more obscure personalities, Mazzocca says. Everhard Jabach acquired collections from the Ludovisi in Rome and England’s King Charles I. Joachim Heinrich Wilhelm Wagener, whose 262 works constituted the biggest private collection of contemporary works in Prussia, formed the basis of the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin.

Giorgio Morandi’s Natura Morta (1946) © Giorgio Morandi by SIAE 2022; © Federico Manusardi

The show’s venue, in the lavishly decorated headquarters of the former Banca Commerciale Italiana (Comit), is symbolically significant. The space now serves as one of four Italian museums in the Gallerie d’Italia network, created by the Intesa Sanpaolo bank to display its own art collection. “With its museums, Intesa operates the kind of cultural approach we explore through this exhibition,” Mazzocca says.

The exhibition closes with a section dedicated to Raffaele Mattioli, the so-called “humanist banker”, who played a leading role in orchestrating Italy’s post-war economic and cultural revival. Mattioli battled to preserve the country’s artistic heritage, buying Michelangelo’s Rondanini Pietà (1564) for the city of Milan, to avoid its expatriation to the US, and starting the art collection of the Comit bank, which he directed. He also actively supported established artists such as Renato Guttuso and Morandi, by commissioning and buying their works both privately and through the bank.

When Comit fused with other banks in the late 1990s to form the current Intesa Sanpaolo, its art collection became the basis of what is now displayed in the Gallerie d’Italia. The link between the museums and Mattioli is embodied in Morandi’s Still Life (1946), commissioned by the banker, which is being exhibited in public for the first time and closes the show. “This exhibition has been a rare opportunity to study Mattioli,” Mazzocca says. “Nobody had realised quite how much he had done for art.”

• Patrons, Collectors, Philanthropists: from the Medici to the Rothschilds, Gallerie d’Italia, Milan, until 26 March 2023