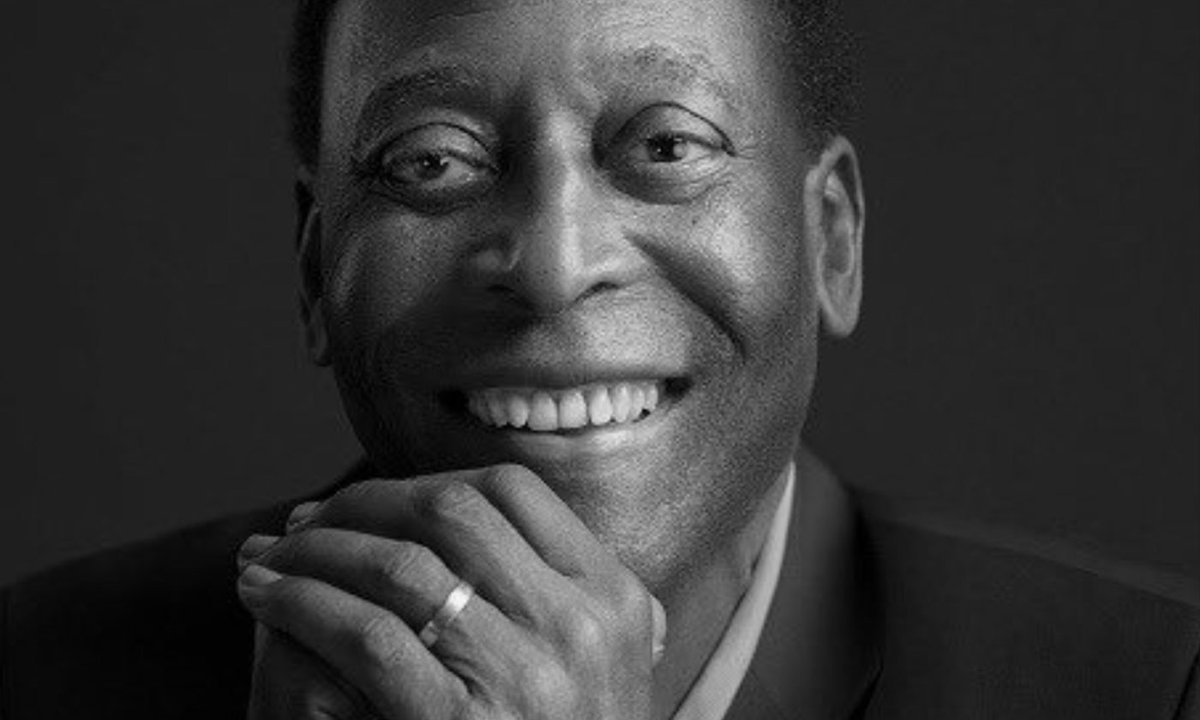

Pelé, the Brazilian football legend who transcended sport and turned the “Beautiful Game” into an art form, has died, aged 82.

The Brazilian forward was the greatest footballer of all, and the only man to win three World Cups—in 1958, 1962 and 1970. Like his friend Muhammad Ali, Pelé became a global figure, instantly recognisable in the golden age of television and early jet travel. Like Ali, he was one of the first Black global sporting stars, who rose from poverty in a racially segregated world, and who had an appeal to every level of society beyond his extraordinary sporting achievements.

Pelé was portrayed by artists including Andy Warhol, Martin Parr, Juergen Teller, Elaine de Kooning and the rock star Ronnie Wood, and the subject of some of the most indelible sports photographs of the 1960s and 1970s. “Pelé was one of the few who contradicted my theory,” Warhol once said, “instead of 15 minutes of fame, he will have 15 centuries.”

“I became art by the talent of my friend Andy Warhol. We got along immediately, despite language barriers,” Pelé tweeted in 2020 twitter.com/pele

Pelé was known for the elegance and effectiveness of his game. His effortless speed across the pitch, deft ball control and power off the ground and in the air, saw him score 1,283 goals in 1,366 matches for his clubs, Santos and New York Cosmos, and for Brazil. To the World Cup-winning England captain Bobby Moore, Pelé was the complete player, a man who was “Only 5ft 8in tall, yet he seemed a giant of an athlete on the pitch. Perfect balance and impossible vision. He was the greatest because he could do anything and everything on a football pitch.”

In 1958, aged 17, he became the youngest-ever winner of a World Cup tournament and the youngest scorer in a World Cup final. In the 1970 World Cup, in Mexico, the first to be broadcast to a global audience, and the first on colour television, he starred as conductor and star soloist of a matchless Brazil side who, sporting the national colours of gold and cobalt blue, played the sport with the grace and improvisatory flair worthy of a great musical ensemble.

Pelé was one of the few who contradicted my theory. Instead of 15 minutes of fame, he will have 15 centuries

Andy Warhol

Following Pelé’s death, the arch at Wembley stadium was lit up in blue and gold, as was the statue of Christ the Redeemer overlooking the city of Rio de Janeiro, while NASA marked the footballer’s passing with a photograph of a spiral galaxy in the constellation Sculptor in the colours of the Brazilian team.

Pelé’s special appeal was his demonstrable sportsmanship and integrity, his approachable nature, and easy smile, which made him a natural diplomat for sport and country, one who was received by monarchs and presidents around the world. “Absolutely everybody wanted to shake his hand, to get a photo with him,” the rock star Mick Jagger once said. “Saying you had partied with Pelé was the biggest badge of honour going.” The US President, Joe Biden, said following Pelé’s death: “For a sport that brings the world together like no other, Pelé’s rise from humble beginnings to soccer legend is a story of what is possible.”

Pelé’s grace and flair on the pitch, and his propensity for scoring with bicycle kicks, made him the subject of some spectacular action photographs. (The trademark bicycle kick features in his performance in the 1981 Second World War prisoner of war drama Escape to Victory, directed by John Houston and co-starring Sylvester Stallone, Michael Caine and Max von Sydow.) But it is telling that the two most memorable photographs of Pelé are emblems of sporting camaraderie, taken in moments of recollection once the action is concluded.

On 7 June 1970, Brazil played a World Cup group game against England in Guadalajara. It was one of the matches of the tournament, which Brazil won 1-0, where an unstoppable header from Pelé was somehow beaten away by the England goalkeeper Gordon Banks, and after which both teams later proceeded to the knockout stages. After the game, the photographer John Varley, of the Daily Mirror newspaper, followed the England captain Bobby Moore around the pitch in the hope that he might see Moore interact with Pelé. He photographed the two players just as they exchanged shirts and embraced. The photograph captures a moment of respect, admiration and affection.

“That photo has gone around the world,” Pelé later said. “I think it was very important for football. We demonstrate that it’s a sport. Win or lose, the example, the friendship, you must pass these on to the next generation.”

Pelé retired from football in 1974, hanging up his boots at Santos, but the following year he accepted an irresistible offer to play for New York Cosmos, an all-star team in New York City, where his presence between 1975 and 1977 generated sell-out stadiums in a country that was taking its first steps in “soccer”.

On 1 October 1977, Pelé appeared in what really was his final game, in an exhibition match at New Jersey’s Giants Stadium, between his two clubs, Santos and New York Cosmos, in which he played one half for each side. President Jimmy Carter and Muhammad Ali and Bobby Moore were in the watching crowd of 77,000 and afterwards Ali came on to the pitch and was given the match ball by Pelé. The moment that they embraced—Ali facing the camera; Pelé with his No 10 Santos jersey seen from behind—was captured by an unknown photographer.

It is telling that the two most memorable photographs of Pelé are emblems of sporting camaraderie, taken in moments of recollection once the action is concluded

That moment of unaffected amity between Ali and Pelé has spawned street art around the world with variations in which they figure embracing Pelé featuring anyone from David Bowie, to Paul McCartney and the Mona Lisa.

Football as a museum staple

The exchange of shirts between Moore and Pelé in 1970 marks an early stage of the phenomenon in which sport, and in particular football, became a high-end collectible and staple of museum shows. The highest ambition of today’s football stars—the No 10s who follow in the footsteps of Pelé and the late Diego Maradona, including Cristiano Ronaldo, Lionel Messi, and Kylian Mbappé—is to honour the sport’s history through collections of historic shirts and football boots, and to acknowledge the inspiration that Pelé has provided for their careers.

There is a substantial Pelé museum in Santos, replete with photographs, shirts and ancient leather boots that act as a reminder of the heavy balls and footwear which Pelé had to contend with when weaving his magic on pitch half a century ago.

In 2015, Pelé: Art, Life, Football, a show of art and photographs inspired by the footballer was shown in London, at the Halcyon Gallery—featuring Warhol’s painting of Pelé for his 1977 series Athletes—one that formed the basis of an exhibition at the National Museum of Football in Manchester. In the lead-up to the 2018 World Cup, the Pérez Art Museum Miami mounted The World’s Game: Fútbol and Contemporary Art, a show of 50 works that included Warhol’s image of Pelé.

Four years later, the World Cup in Qatar opened with the news that Pelé was seriously ill with cancer in a São Paulo hospital. The Brazilian team held a giant banner of Pelé across the pitch before their first match, one of the final and boldest visual tributes, broadcast across the world, to a man whose skill and personal example had made football a global visual, and community, phenomenon.

Edson Arantes do Nascimento (Pelé); born Três Corações, Minas Gerais state, Brazil 23 October 1940; Minister of Sport 1995-98; Honorary Knight (United Kingdom) 1997; married three times (two sons, four daughters); died Sao Paulo, Brazil, 29 December 2022.