Of the many photographs documenting Martin Luther King, Jr.’s acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, one stands out for its quiet intimacy: a closely cropped image of King and his wife, Coretta Scott King, hugging. It was snapped during a news conference, but the couple in the picture could be alone, beaming against a shadowy background in their tight embrace.

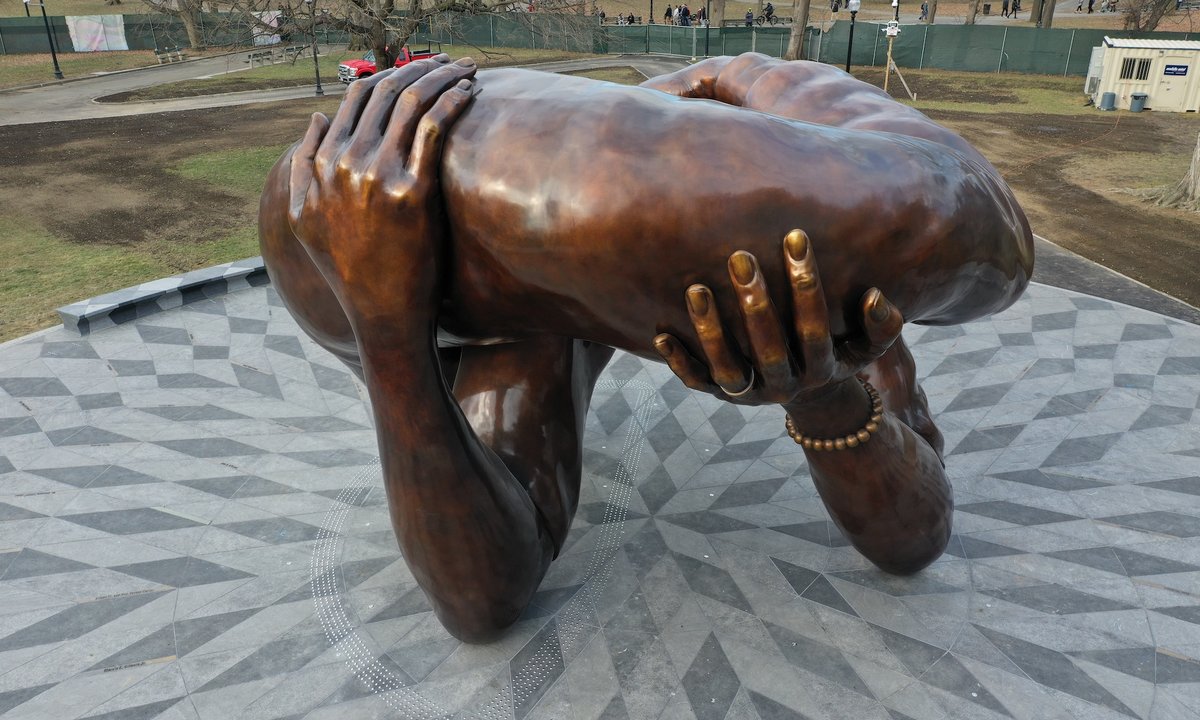

The gesture caught the attention of Hank Willis Thomas, who has closely replicated it in his latest public artwork. Titled The Embrace (2023), the bronze and steel sculpture is a monument to Martin and Coretta that depicts the former’s arms around the latter’s, forming a gleaming, 20ft-tall tripod structure that visitors can stand within. It was unveiled on Boston Common on 13 January, three days before Martin Luther King Day, as the centrepiece of a new plaza honouring civil rights leaders active between 1950 and 1970.

“I’d seen a lot of work on the images of Dr. King, but I realised I hadn’t focused on and noticed the way intimacy was present in [the Kings’] relationship—the way that they looked at each other and laughed at each other, walked hand in hand and arm in arm,” Thomas says. “I was really excited to see them hugging and embracing…also, the pride and joy on her face, and the glee and almost a sense of relief on his face.

“It was an opportunity to talk about the bigger story of their relationship and the impact that their love for one another, and their community, had,” he adds.

Hank Willis Thomas, The Embrace, 2023 Courtesy the artist

The Embrace was commissioned by the nonprofit Embrace Boston, which was founded in 2017 with a mission to address racial inequities in Boston through the arts, community work and policy. Intending to honour Dr. King, who had lived in Boston for three years and considered it his second home, the group launched a call for proposals for a permanent public memorial to him. Thomas’s design, created in collaboration with the Boston-based firm Mass Design Group, was selected in 2019 out of 126 submissions based on public feedback and by a committee of artists, curators, educators and community members.

“The connection between The Embrace and the historic photo of Dr. King embracing his wife after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize was such an important aspect of choosing this design,” Imari Paris Jeffries, executive director of Embrace Boston, told The Art Newspaper. “When I look at the monument, I see my parents embracing each other; I see myself embracing my family and friends. I hope this monument allows others to act on their love toward the important people in their lives.”

Thomas, an artist who works across many media, often elucidating unvarnished truths, heard of the commission through his friend Michael Murphy, cofounder of Mass Design Group. They had previously worked together on the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Alabama, where Thomas’s sculpture Raise Up (2014), a row of arms and faces emerging from a stone block, rests on the memorial’s grounds. When Murphy reached out about the Boston project, they had also recently submitted a proposal to design a new MLK branch of the Cleveland Public Library that was not selected. The Boston opportunity felt apt for Thomas, who has also been outspoken in the conversation about the future of monuments across the United States.

Hank Willis Thomas, The Embrace, 2023 Courtesy the artist

“I think about the potential of The Embrace to be an inspiration for what monuments of the 21st century will look like,” he says. “There has been a reckoning and conversation about what’s been done in the past, but really, we’re looking at the past as a gateway to the future.”

The Embrace stands at the centre of a new memorial site called the 1965 Freedom Plaza, where the names of 69 local civil rights leaders selected by the public are inscribed. All of them participated in the Kings’ 1965 civil rights march from Roxbury to Boston Common, according to the Wall Street Journal. Diamond-shaped pavers surrounding the monument, composed of more than 1,300 granite stone pieces, nod to African American quiltmaking traditions.

The memorial is just one of Embrace Boston’s several endeavours to foster social justice in the city, which range from the publication of a “Harm Report” that identifies racial equity gaps in Boston and the construction of a cultural centre for the Black community. Visualising on a grand scale an unshakeable bond, and upholding care as something worth commemorating, Thomas sees The Embrace as a reminder of the grounding on which radical work must be built.

“The aspiration of this piece,” he says, “is that 100, 200 years from now, that, along with the celebrations of the heroes of a war and of democracy and literature, there can be heroes of nonviolence and communal and civic love.”