The estate of the late American photographer Larry Fink, celebrated for his class-conscious black-and-white images of Americans across social strata, has been acquired by the MUUS Collection, a for-profit company dedicated to championing the work of undervalued photographers. The firm will stage an exhibition on Fink curated by the author, critic and artist Lucy Sante at the forthcoming edition of Paris Photo in November, coinciding with the release of a new monograph on the artist’s work.

Fink, who died in November 2023 aged 82, built a legacy producing indelible photographs often suffused by his leftist politics and his deep roots in New York. He gained notoriety beginning in the 1950s for his images depicting the second generation of Beats in Greenwich Village, as well as jazz musicians and activists in the civil rights and antiwar movements. Social Graces, a series that paired shots of Manhattan’s high society with those of his salt-of-the-earth neighbours in rural Pennsylvania, was the subject of an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1979 and was published as a sought-after monograph in 1984. Fink’s work has been collected by the likes of MoMA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. He also frequently worked on assignment for publications such as Vanity Fair, The New York Times and others.

For the exhibition at Paris Photo, Sante—who knew Fink personally, and who has spent her own career engaging with some of the late photographer’s core themes—has selected more than 30 photographs stretching across his six-decade career, including one that she received as a postcard long ago and kept above her desk for years. Most of the featured images revolve around human interactions, highlighting both the empathetic spirit in Fink’s work and his distinctive aesthetic. The MUUS (pronounced “muse”) Collection is also supporting a separate exhibition of Fink’s work scheduled to open at the Sarasota Art Museum in Florida in November.

Fink’s estate was purchased for an undisclosed price of more than $1m, according to a spokesperson for the MUUS Collection. It is the sixth estate the firm has acquired to date, preceded by those of the photographers Rosalind Fox Solomon, Deborah Turbeville, Fred W. McDarrah, Alfred Wertheimer and André de Dienes. The firm also owns two other large bodies of photographs that it classifies as “collections”: around 100 experimental photographs by the former advertising executive William Richards, and the Semple Portfolio of Notable American Women, a compendium of portrait photos and signed letters from distinguished women in the US compiled by the publisher James Alexander Semple in the 1920s. Altogether, the MUUS Collection’s archive comprises around 1 million images.

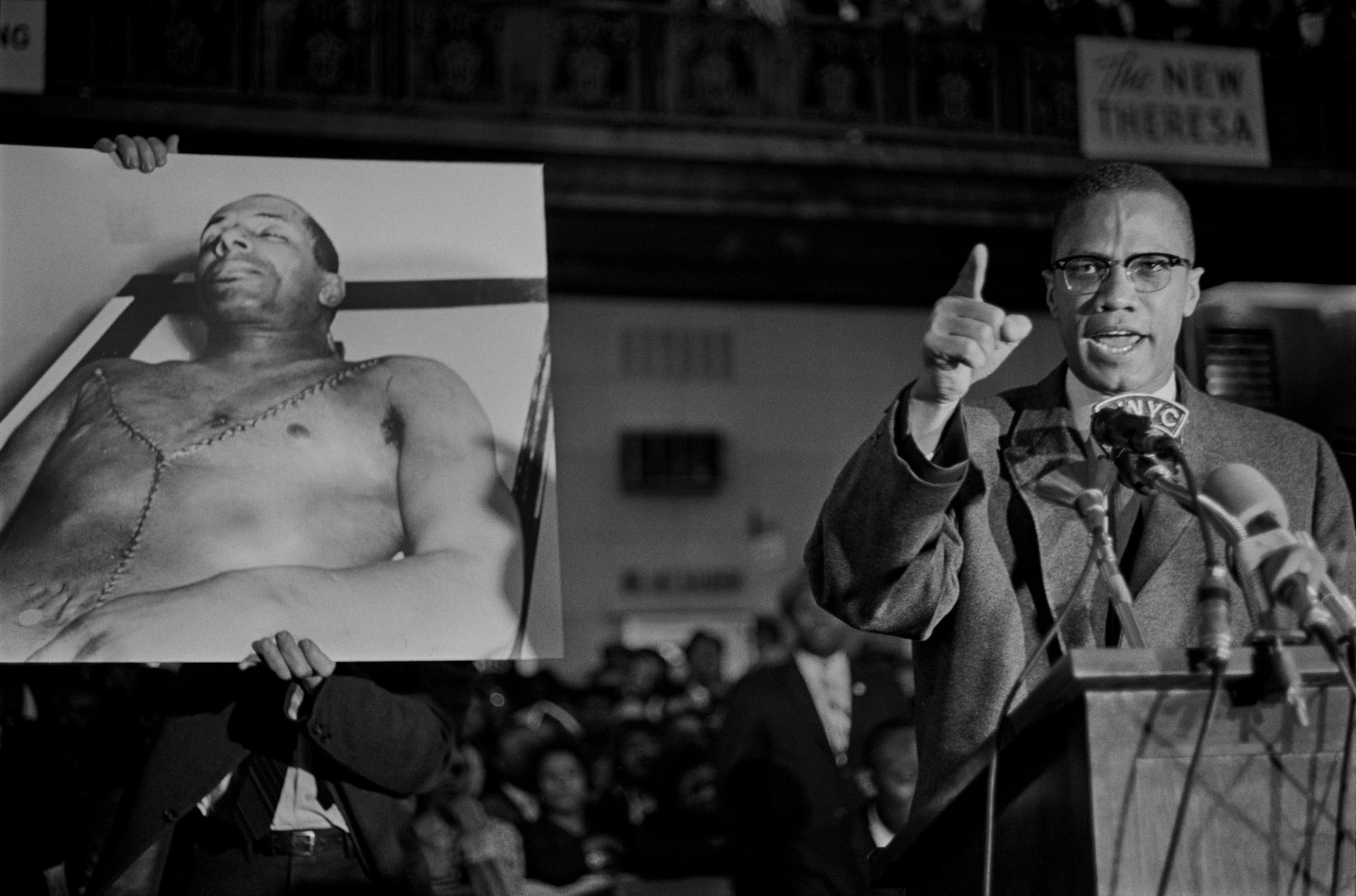

Larry Fink, Malcolm X, Harlem, NY, May 1963 (1963)

Courtesy of The MUUS Collection

From chance purchase to collecting strategy

The MUUS Collection was founded around a decade ago by Michael W. Sonnenfeldt, a US-based property developer turned serial entrepreneur and venture capitalist with a focus on the alternative energy space. (The name MUUS is a stylisation of his initials.) Although he has been a photography enthusiast for decades and a published photographer himself, Sonnenfeldt tells The Art Newspaper that the Collection owes its existence largely to happenstance.

The unexpected spark came around 30 years ago, when he acquired an intact album of 87 photographs of Jerusalem shot in the 1850s by a Scottish missionary called James Graham. Sonnenfeldt originally expected that he could simply hold the album for some time and resell it for a profit. “But as so often happens, no one ever came to look at the album,” he says. “Fifteen years went by, and I still had it on my shelf.”

His interests eventually compelled him to initiate a robust research effort that “put the album in a unique historic context”. When his family later decided to donate the album jointly to the Israel Museum and the Center for Jewish History in New York, he adds, “We got it appraised, and it became clear the album was worth many times what we’d paid for it”.

This led to a small revelation, Sonnenfeldt says: “I simply observed there was something different about buying many photographs than buying one photograph. Obviously, when you’re buying 1,000, you’re not paying 1,000 times the price of one photograph.”

After purchasing Graham’s Jerusalem album, Sonnenfeldt went on to acquire a few portfolios by other photographers that ranged in size from around 100 images each to around 1,000. This scale-up led to the establishment of the MUUS Collection and, with it, Sonnenfeldt’s realisation that “there was something magic about purchasing entire estates”. The bulk discount, as it were, was far less of a draw to him than the insights such collections provided into the artists, their practices and the themes and circumstances informing their most well known images.

Yet it is important to distinguish what “images” means in the context of a photographer’s estate. The MUUS Collection’s purchases encompass not only the existing physical works but also the intellectual property (IP) and copyright behind them. The holistic package equips the firm with everything it needs to create new exhibitions, publications, documentaries and any other projects that able to enhance the public’s understanding of, and esteem for, its artists.

This is easier said than done, however. When a collector acquires a photographer’s estate, Sonnenfeldt says, “you don’t know what you’re buying”. Fink’s, for instance, consisted of “three 30-foot truckloads of materials”, some of which “had been in boxes for 30 years and nobody had ever looked at them”. In other cases, he says, “you might buy the rights to the work even though the negatives might be somewhere else. You might buy prints, or the prints might be somewhere else”. Whatever the contents, they must be painstakingly inventoried, organised, condition reported and studied to be fully known.

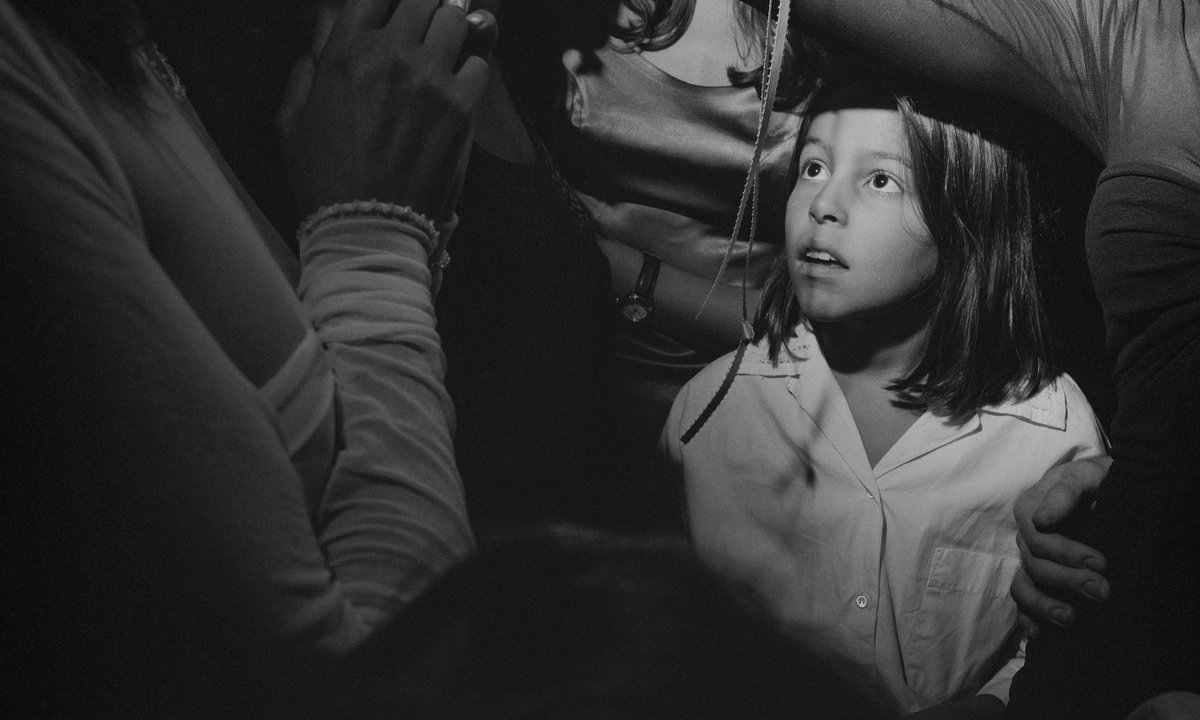

Larry Fink, Dance, American Legion, Bangor, PA, March 1979 (1979)

©Larry Fink/MUUS Collection, courtesy MUUS Collection

An unusual paradigm

This challenge required the MUUS Collection to build a team of in-house and external specialists, including archivists, historians, digitisers and more. The firm currently employs eight staff (though not all are full-time): two based in Europe, and six based in New Jersey, where its archive is located. Sonnenfeldt says that, on average, the firm expects the process of researching and organising each estate to take between five and ten years.

The results have been eye-opening in each case. The MUUS Collection’s deep dive into the Turbeville estate, for example, led to the discovery of her Passport series, around 120 collages that had never before been exhibited until the firm’s involvement, Sonnenfeldt says. Its research into Wertheimer archives turned up the entire series of images from which the photographer plucked The Kiss, one of the most famous (and mysterious) frames of Elvis Presley ever captured. The estate of McDarragh, the longtime photo editor of The Village Voice, contained his images of what Sonnenfeldt calls “the Rosa Parks moment of the gay rights movement”, when a Manhattan bartender frantically covered the glasses of three business-suited male customers he had just served moments before one of them declared he was gay. McDarragh had worked with the men to stage the encounter for the camera, and his photograph of the event—which took place in 1966, three years before the Stonewall Uprising—was later submitted as evidence in the case that ended New York’s laws banning openly queer customers from bars.

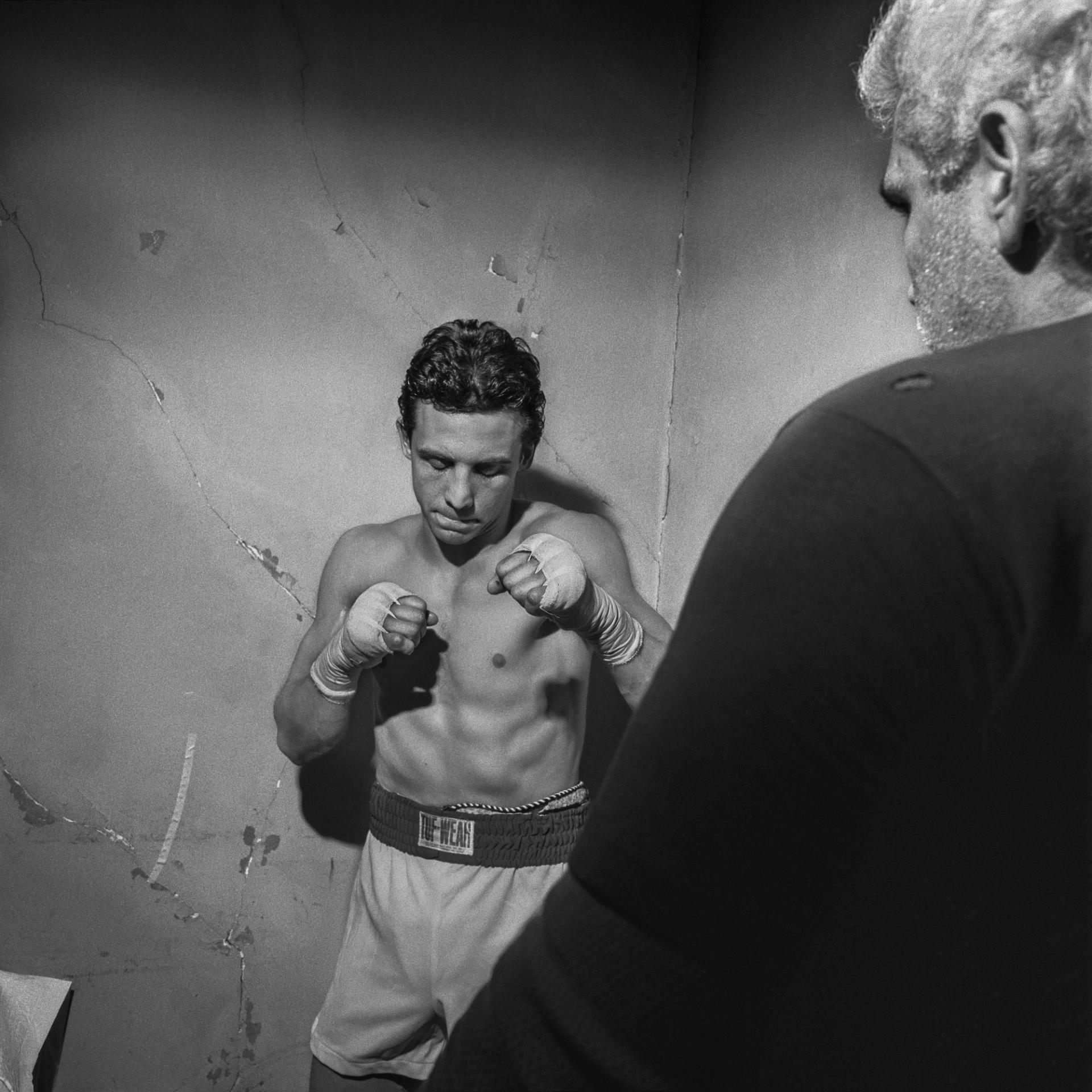

Larry Fink, Boxer, Blue Horizon, Philadelphia, PA, January 1990 (1990)

©Larry Fink/MUUS Collection, courtesy MUUS Collection

“Larry had come to us when he was alive because he’d heard from galleries that if you wanted to find a buyer who was going to honour the legacy, we were literally the only people doing what we’re doing,” Sonnenfeldt says, referring to the origin of the deal between Fink’s estate and the MUUS Collection.

The firm will have played a direct role in organising six exhibitions worldwide by the end of 2024, including the two Fink shows. The full lineup spans commercial and institutional venues ranging from Christophe Gaillard Gallery in Paris and Pace Gallery in Geneva to the New York Historical Society and The Photographers’ Gallery in London.

What the MUUS Collection does is easier to grasp than the firm’s categorisation. In several respects, it resembles many US-based private art foundations—legal entities each funded by a single individual and devoted to studying, exhibiting and promoting a single collection—except that it is incorporated as a for-profit company and seeks to monetise its holdings at some future juncture. (Sonnenfeldt says “only a small portion of” the MUUS Collection’s operating revenue comes from the fees it is paid by Getty Images and similar photo-licensing platforms for the works of its artists that are available there.)

The MUUS Collection also shares several traits with a commercial gallery, but that paradigm too is a poor fit for its overall mission. The collection has no permanent exhibition space, continuous programme or representation agreements with artists and estates. Instead, it owns the estates outright and keeps its sights set on the long-term view.

“A gallery has to break even each year. We’re untethered from that normal business constraint,” Sonnenfeldt says. “Fundamentally, we’re still a collection being underwritten by a private collector. The difference is, we’re part of a small minority of collectors, where, by having large collections and staff and activities, you actually transform the collection.”

“We’re not just buying and holding and selling. What we’re most excited about is the work we do… to reveal certain themes and insights about the artists, and the time and the events that they were capturing,” he says. “We’re not burning dollars. We’re trying to build extraordinary value.”