When young men and women stepped into studio backdrops to have their photograph taken in Bamako, Kinshasa and Accra in the 1950s and 60s, they were doing more than dressing up for the camera. With their pressed suits, patterned dresses, sunglasses and poise, they were performing independence.

This idea is central to a survey of West and Central African portrait photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Bringing together dozens of such scenes, it suggests these pictures did something larger still: they helped shape a political imagination for Black people on either side of the Atlantic, forging new freedoms and identities.

Ideas of Africa: Portraiture and Political Imagination shows studio portraits by James Barnor, Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, with later works by Jean Depara, Sanlé Sory and Kwame Brathwaite, alongside contemporary works by Samuel Fosso, Silvia Rosi and the collective Air Afrique, to name a few. Seen together, they portray an emergent language of confident optimism that travelled from newly independent African countries to the streets of London and New York.

The framework for the show—asserting an Africa that produced its own wisdom and meaning—was inspired by the Congolese author V.Y. Mudimbe’s 1994 book The Idea of Africa, which dissected how the West constructed a concept of the continent. The exhibition aims to treat studio photography not as documentary record but as a form of authorship, an imaginative act in which Africans defined themselves on their own terms.

Pan-African transmission

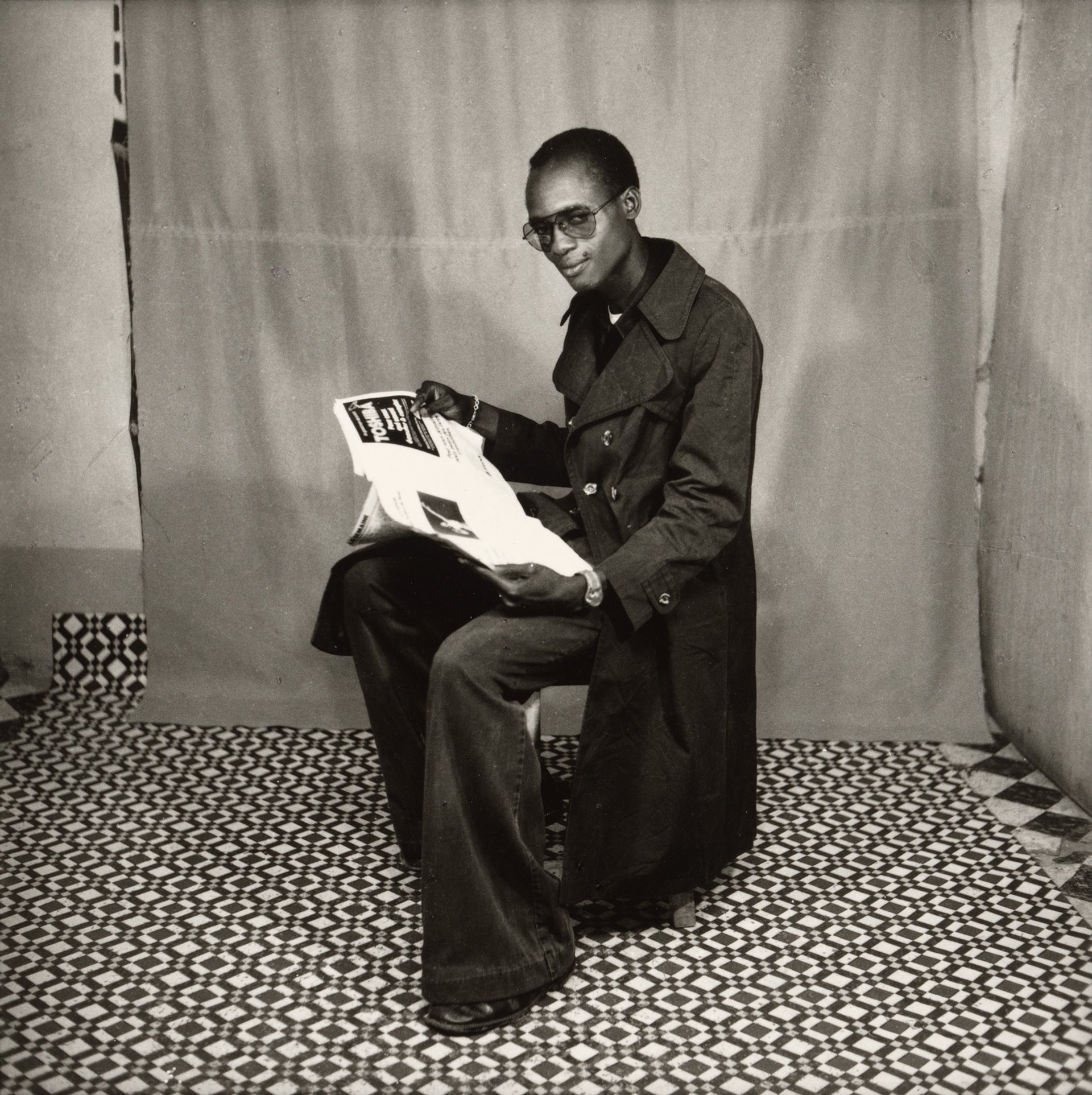

Sanlé Sory’s Intellectual (L’Intellectuel) (1970-85) © MoMA, New York

“In focusing on imagination, I’m encouraging people to be attuned to the interpretive potential of a photographic portrait, not solely its documentary utility,” says the MoMA curator Oluremi C. Onabanjo. “For me, the inclusion of work by Brathwaite and Barnor, as well as the transgenerational iterations of Air Afrique, speaks to the literal transmission of Pan-African ideas and images across space and time.”

The mid-1950s to mid-60s were charged with optimism—17 African nations gained independence in 1960 alone, while the civil rights movement was transforming the US. Portraits by Keïta or Sidibé conveyed that exhilaration, but Onabanjo argues that they also circulated widely, feeding a broader sense of connection. In the exchange between Barnor’s work in Accra and London and Brathwaite’s images of the “Black is Beautiful” movement in New York, Onabanjo traces a transatlantic call-and-response helping shape ideas of Pan-African pride.

A reading room in the show illustrates how the flowering of print culture carried these images beyond the studio. Contemporary works in the show help continue the dialogue.

Rather than nostalgia, Ideas of Africa proposes a more dynamic reading of these pictures as evidence of how independence looked and was imagined. In their confident gazes and glamour, the sitters were picturing a different world.

• Ideas of Africa: Portraiture and Political Imagination, Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 25 July 2026