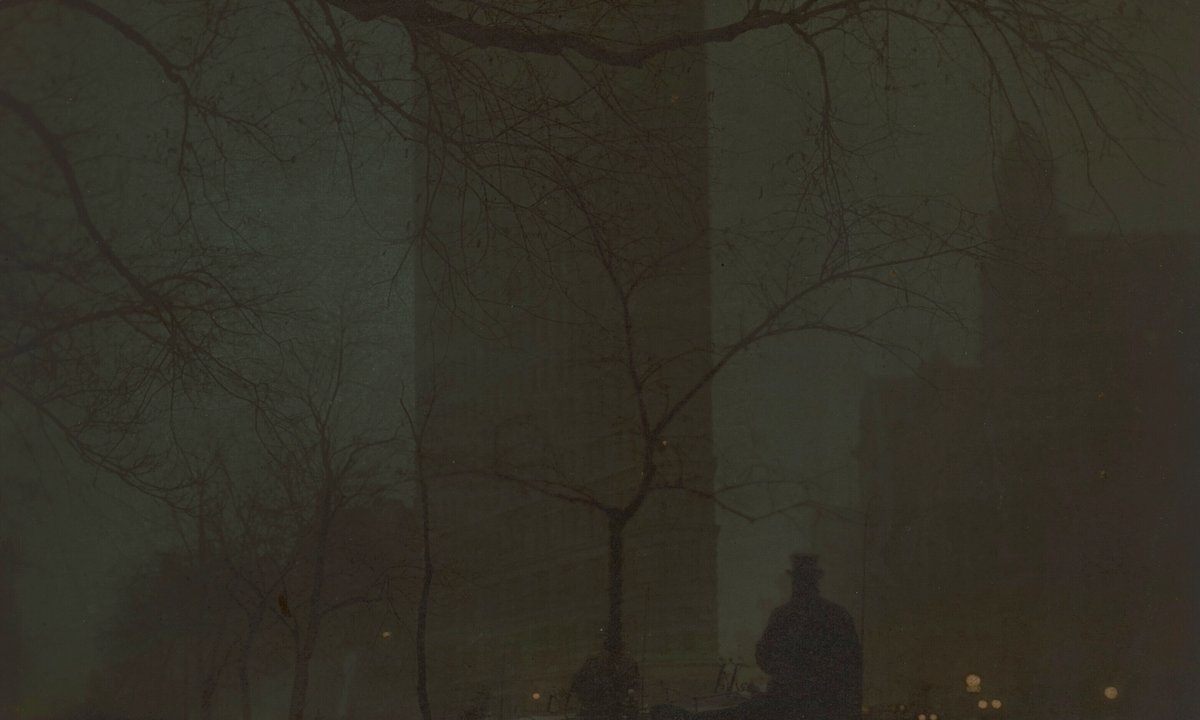

Among the wealth of art in Christie’s forthcoming sales of works from the collection of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen in New York (9-10 November), there is a photograph that some think has enormous potential. Edward Steichen’s The Flatiron (1904, printed 1905) comes with an estimate of $2m-$3m, but given its rarity and importance in the photography community as a harbinger of the medium’s artistic possibilities, the expectations are high.

Some at the auction house believe it could surpass the record for a photograph, set just this May when a print of Man Ray’s seductive Le Violon d’Ingres (1924) sold for $12.4m (with fees). That sale was also at Christie’s, and the Man Ray came with a $7m high estimate thanks, in part, to resurgent collector interest in Surrealism and the iconic nature of the subject, the naked back of Kiki de Montparnasse with violin f-holes painted on either side of her lower back.

Man Ray’s Le Violon d’Ingres (1924) sold at auction earlier this year for $12.4m, smashing the previous auction record for a photograph. Courtesy Christie’s

The Flatiron may not have the sex appeal of Le Violon d’Ingres, but it is just as historically relevant—if not more. The picture was taken just two years after the Flatiron Building was finished, a sign that modernity was flourishing in New York. It was also a response to a photograph by Steichen’s mentor and comrade Alfred Stieglitz, who had photographed the building the year before. There are only three prints of the image in existence, two of which are in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection. And all three are different, thanks to Steichen’s use of gum bichromate over the platinum print, which gave each print a different hue.

The print headed to auction stayed in Steichen’s family until the 1990s, and was acquired by Allen in the early aughts. It has been lauded by photography aficionado’s as one of the first examples of photography’s ability to match painting as an art form.

“Steichen is working still in this sort of pictorialist tradition that is, in a way, mirroring visual language of the arts of the day,” says Darius Himes, international head of photography at Christie’s. “This is honestly his most iconic image. And one that he was so proud of because it really represents Steichen at the height of his youthful powers.”

The record-breaking sale of Le Violon d’Ingres was proof the photography market is on its way up after years of relative stagnation. But not everyone is convinced that The Flatiron can command as high a price as Man Ray’s risqué composition. “If you were to put two doors outside a museum, and outside on the left there was a sign that read, ‘Pay 20 bucks to come and see the Man Ray,’ and on the right, ’20 bucks and come see the Steichen,’ you’re going to have two very different-looking queues,” says Michael Hoppen of the namesake London gallery, which specialises in photography.

However, the art market has in some ways always been about trophy-buying, and rarity can be as important a factor as the familiarity of an image. “It comes down to what the bidders and eventual buyer is looking for,” Hoppen says. “Aesthetic love? Rarity? A trophy? All are possible and if The Flatiron does pass the record set by the Man Ray, that would mean a great deal for the photography market.”