After the hard right party Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d’Italia, BOI) swept to power in the country in September, it appointed the veteran journalist Gennaro Sangiuliano as the country’s culture minister. Sangiuliano has hinted at a new era of cultural identity politics, pledging to “open culture to all Italians, who must feel like inheritors of a great tradition”.

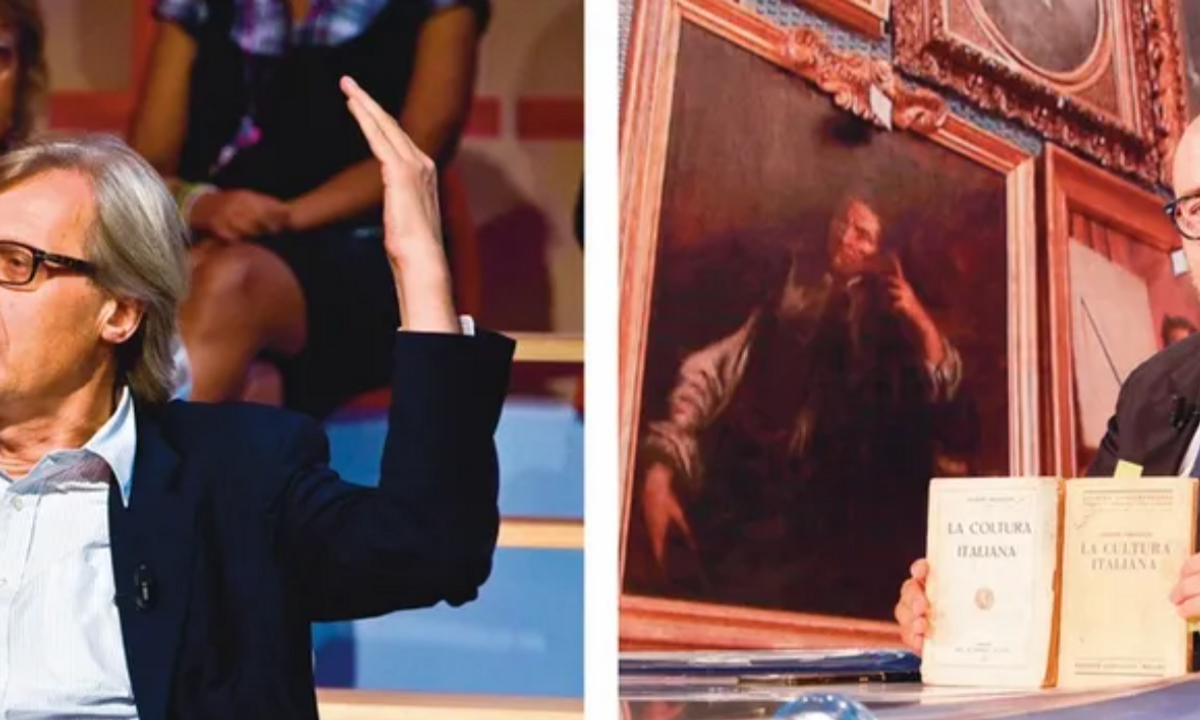

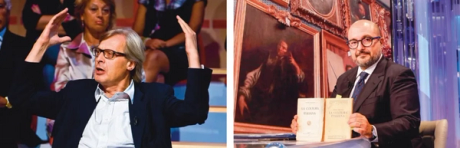

Yet one of his three undersecretaries, the powerful and unpredictable art critic Vittorio Sgarbi, has pushed a different agenda, that of conserving Italy’s vast heritage and introducing free entry at museums, ultimately raising questions about where Italy’s culture policy is headed.

During the election campaign, BOI, which is led by firebrand politician Giorgia Meloni, defined culture as a “cardinal strategic point”, noting that the country’s arts industry generates roughly €85bn annually. The party promised to wipe out a left-wing “cultural hegemony” within arts institutions, punish those who vandalise heritage and cut museum ticket prices to attract visitors.

Sangiuliano has defined Italy as a “cultural superpower” since his appointment to the ministry in November. He has also expressed surprise that the country’s top museums are directed “mainly by foreigners”, and suggested that Rai, the Italian public broadcaster with which he was previously employed, should transmit more programmes about right-wing historical figures.

‘An absolute good’

Sgarbi has floated an array of his own policies, demanding that long-standing plans for a new Arata Isozaki-designed exit to be built at the Uffizi museum in Florence be dropped (even though the government has already allocated €12m for the project); denouncing proposals to replace Donatello’s Gattamelata bronze (1453) in Padua to preserve the original; and demanding that Michelangelo’s Rondanini Pietà (1552-64) be moved from one part of Milan’s Castello Sforzesco to another. The latter proposal has been dismissed by the city’s mayor.

Sgarbi appears to have tried to differentiate himself from the minister. “[Sangiuliano] is conservative in the political sense, which is a partisan position, while I promote conservation, which is an absolute good,” he said. He added that he and Sangiuliano “agree on nine things out of ten”.

However, the two figures have also publicly clashed. Speaking on Rai radio in November, Sgarbi reiterated his historic demand for museums to be made free to Italians while maintaining entry fees for tourists. Sangiuliano responded on a Rai television talk show later in the day, declaring: “I am completely against the idea of free museums, which would weigh on the national budget and diminish the value of the works [on display].” But Sgarbi tells The Art Newspaper: “I think the [free museums] idea will ultimately pass [through parliament],” adding, “We need to get Italians used to the idea of going to museums.”

The two figures have also disagreed over plans to protect art from ongoing protests by climate activists. In a press note circulated in November, Sangiuliano suggested that museum ticket prices could even be increased to pay for protective glass panels to be placed over paintings. The hike would also allow for security forces to be strengthened, Sangiuliano said.

Sgarbi hit back shortly after, on a Radio Capital programme, calling the plans “impossible to realise” and declaring that “paintings look good without glass”. The critic also argued that it would be better to confiscate damaging materials from protesters before they are taken into museums. No concrete measures had been announced by the time that The Art Newspaper went to press.

Whichever vision ultimately dominates, it could mark a departure from that of Dario Franceschini, the Democratic Party veteran who has served as Italy’s culture minister for almost all of the last eight years.

The former minister’s sweeping reforms were frequently criticised by experts and commentators as being geared more towards improving museum visibility and visitor numbers than safeguarding heritage. These included granting major state-run museums greater autonomy, opening up museum managerial positions to international figures, and backing headline-grabbing initiatives, such as that to rebuild the original arena floor at Rome’s Colosseum.

“Some of Franceschini’s experiments basically failed. All of the focus was on the big museums, while small institutions were left to the regional administrations,” Michele Campisi, the museums and art spokesman for the heritage conservation organisation Italia Nostra, says. “Sgarbi shares our way of looking at heritage. There are monuments and archaeological parks that drastically need attention,” he adds.